2022-2023 Stanford Distinguished Professors

2022-2023 Stanford Distinguished Professors

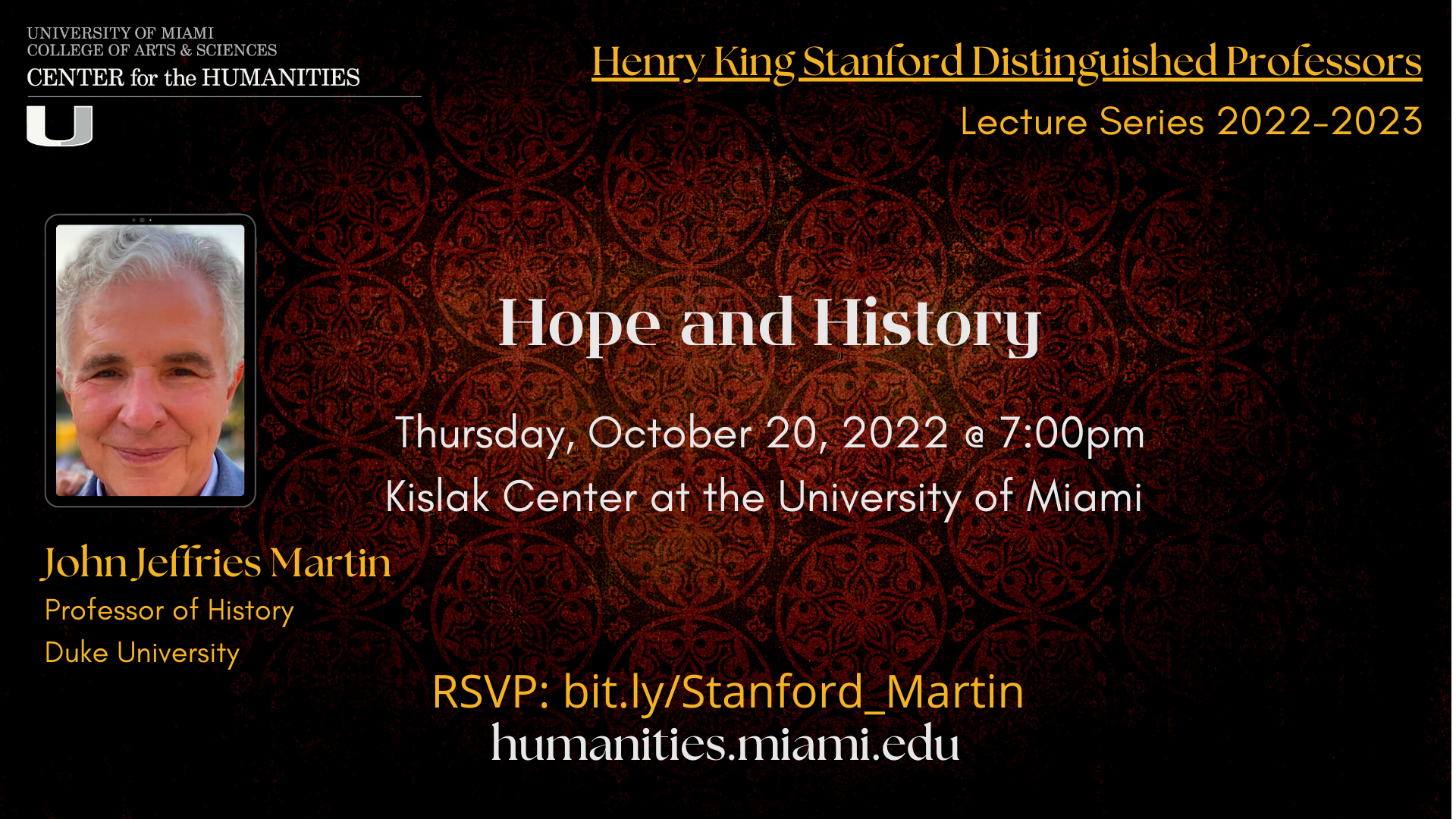

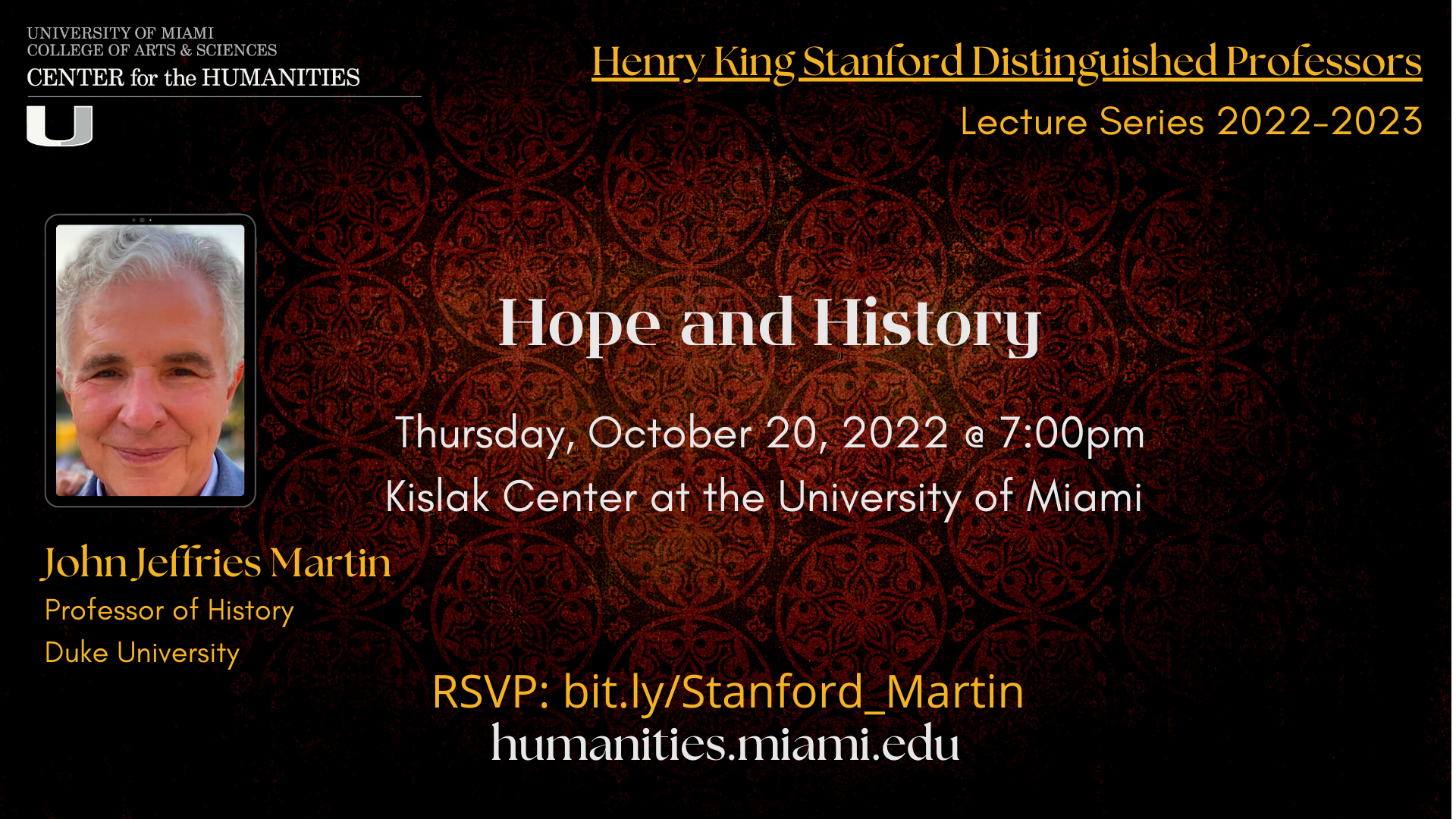

Thursday, October 20 @ 7:00 pm, Jay I. Kislak Center, University of Miami Libraries

John Jeffries Martin: "Hope and History"

for recording!

for recording!

In late medieval and early modern Europe people placed their hopes in religious faith, and it was largely providential or even apocalyptic ideas that laid the foundations of the modern world. But in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries a largely secular Idea of Progress became the most prominent reservoir of hopes for the future. But where are we now? The twentieth century witnessed the unraveling of the belief in progress. And today both nuclear weapons and climate change pose existential threats to humanity. As a result, some place their hopes in the transcendent; others in technology; still others in economic, social, and political transformations. Hope, as history suggests, is always lodged in the space between where we are and where we long to be at some point in the future. But hope is not without its costs. Both the expectations of the Apocalypse and the belief in the Idea of Progress led to global inequalities, the violence of imperial repression, and environmental destruction. Is there a form of hope, by contrast, that can lead to a just and sustainable world on a planetary scale?

John Jeffries Martin, professor and former chair of history at Duke, is a historian of early modern Europe. He is the author of Venice’s Hidden Enemies: Italian Heretics in a Renaissance City (1993), Myths of Renaissance Individualism (2004), and editor or co-editor of several volumes, including Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City State (2002), as well of the series Vices & Virtues for Yale University Press. His most recent book, A Beautiful Ending: The Apocalyptic Imagination and the Making of the Modern World, places its emphasis on the role of faith – not only within Christianity but also within Judaism and in Islam – in animating individual and collective actions in the early modern world. Indeed, faith did much to shape agency, and played a role in fostering new political, religious, and scientific visions of a more hopeful future. At the same time, many horrors – from civil wars to colonialism -- also stemmed from the “apocalyptic imagination.”

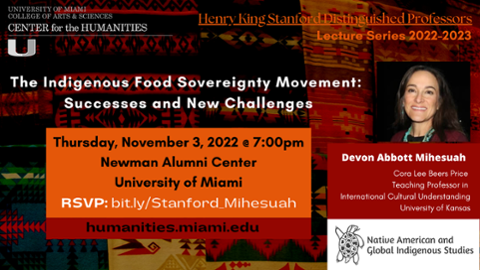

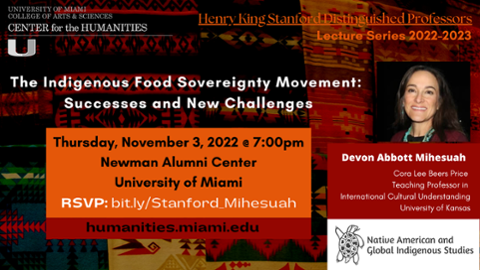

Thursday, November 3 @ 7:00 pm, Newman Alumni Center, University of Miami Gables Campus

Devon Mihesuah: "The Indigenous Food Sovereignty Movement: Successes and New Challenges"

The Indigenous Food Sovereignty Movement (IFSM) is complicated. The overarching goal of the IFSM is for tribes to achieve control over their food systems. The IFSM has exploded in recent years with initiatives such as tribal and grassroots food initiatives, farms, community and backyard gardens, food summits and school programs. Despite these efforts, high rates of diabetes, obesity and other health issues still remain, and food insecurity is a reality for many Natives. The IFSM should involve political, economic, social, religious and environmental activism. This talk provides an overview of what strategies have worked, but more importantly, what has not and what we should do now.

Devon Mihesuah, an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, is the Cora Lee Beers Price Professor in the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas and is the former editor of the American Indian Quarterly and the University Nebraska Press book series, “Contemporary Indigenous Issues.” A historian by training, she is the author of numerous award-winning books on Indigenous history and current issues, including Recovering Our Ancestors’ Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness, that was recently named the Best Indigenous Book in the World by Gourmand International; American Indigenous Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism; Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero; Choctaw Crime and Punishment: 1884-1907 and American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities, as well as seven novels, most recently Dance of the Returned that was published in September 2022. She oversees the American Indian Health and Diet Project at https://aihd.ku.edu/ and the Facebook page, Indigenous Eating. See her blog at: https://devonmihesuah.blog.ku.edu/

Devon Mihesuah, an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, is the Cora Lee Beers Price Professor in the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas and is the former editor of the American Indian Quarterly and the University Nebraska Press book series, “Contemporary Indigenous Issues.” A historian by training, she is the author of numerous award-winning books on Indigenous history and current issues, including Recovering Our Ancestors’ Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness, that was recently named the Best Indigenous Book in the World by Gourmand International; American Indigenous Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism; Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero; Choctaw Crime and Punishment: 1884-1907 and American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities, as well as seven novels, most recently Dance of the Returned that was published in September 2022. She oversees the American Indian Health and Diet Project at https://aihd.ku.edu/ and the Facebook page, Indigenous Eating. See her blog at: https://devonmihesuah.blog.ku.edu/

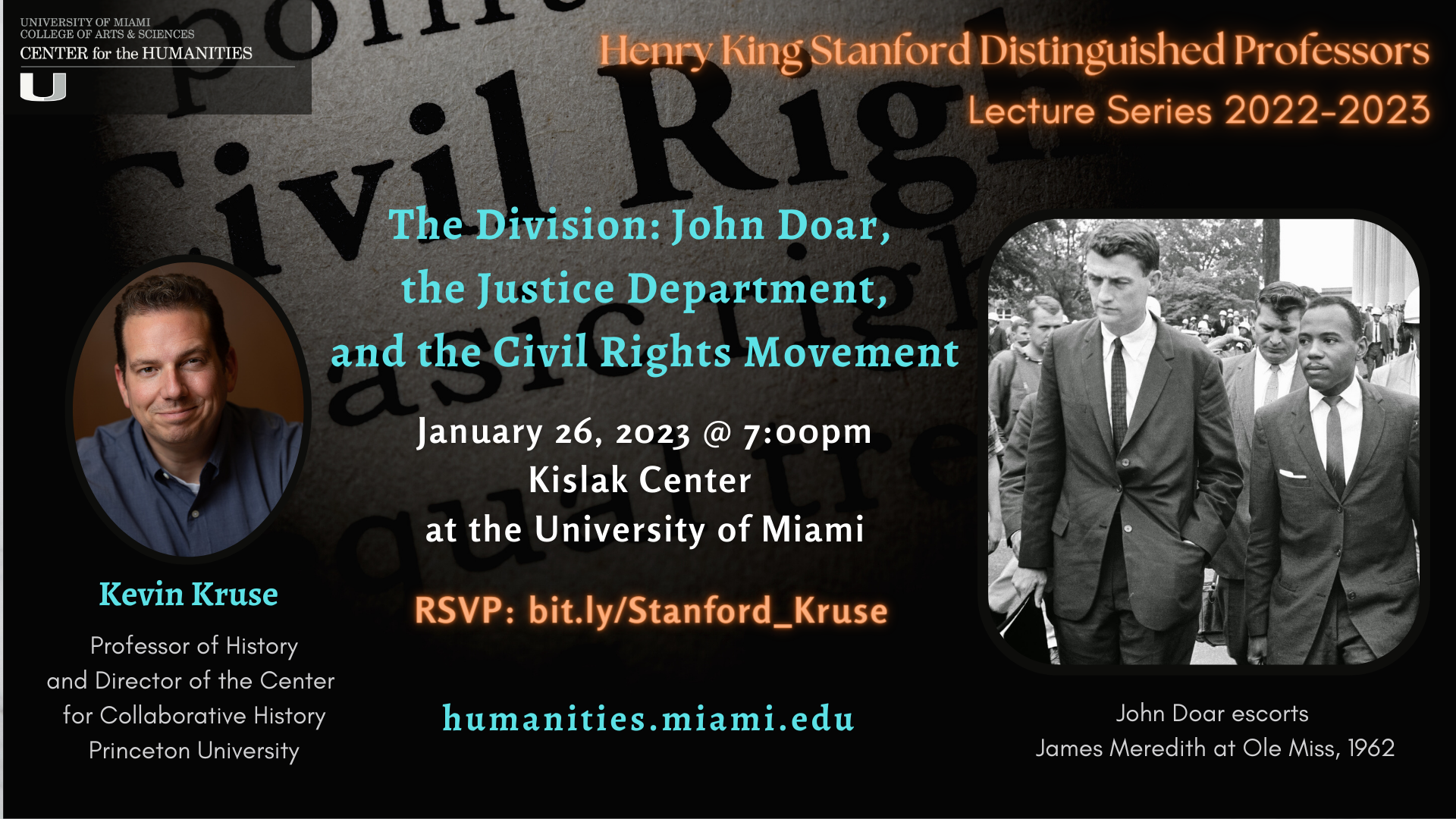

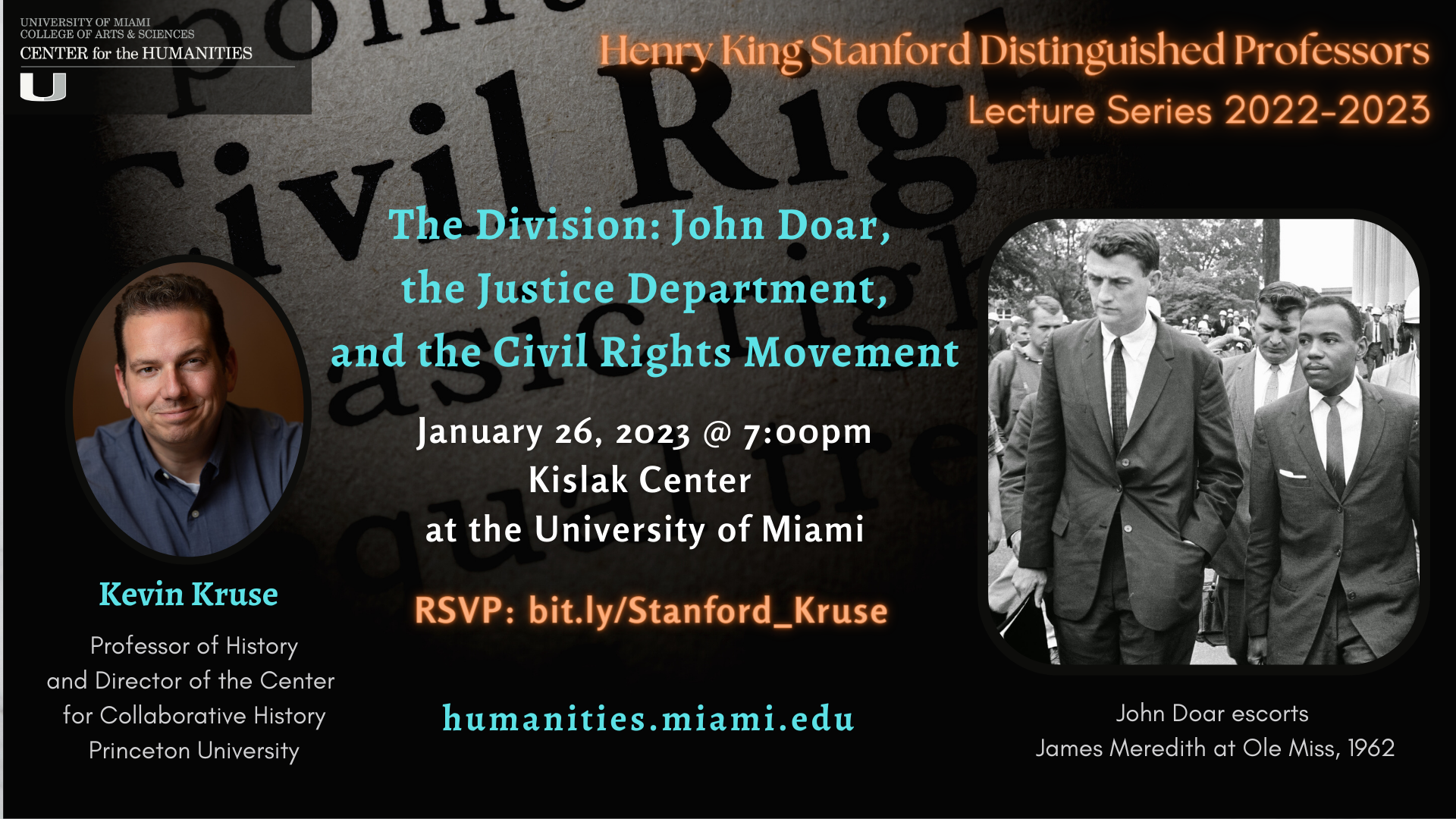

Thursday, January 26, 2023 @ 7:00 pm. Kislak Center at the University of Miami

to view recording!

to view recording!

Kevin Kruse: "The Division: John Doar, the Justice Department, and the Civil Rights Movement"

John Doar was a vital actor during countless crisis moments in the civil rights movement. He worked with Medgar Evers to secure voting rights, protected John Lewis and the Freedom Riders, fought to get James Meredith into Ole Miss, prosecuted Klansmen for the deaths of civil rights workers (including the infamous "Mississippi Burning" murders), oversaw the implementation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and literally led the way in the Selma-to-Montgomery March. Drawing on the previously untapped papers of Doar, Kruse hopes his forthcoming work will not just provide new insights into these civil rights milestones but also provide a new understanding of the ways in which the federal government worked (and didn’t work) during the racial revolution unfolding across the South.

Kevin M. Kruse is Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Collaborative History at Princeton University. He studies the political, social, and urban/suburban history of 20th-century America. Focused on conflicts over race, rights, and religion, he has particular interests in segregation and the civil rights movement, the rise of religious nationalism, and the making of modern conservatism.

Thursday, March 30, 2023 @ 7:00 pm. Kislak Center at the University of Miami

Recording coming soon!

Mabel O. Wilson: "Can We Forget: A Memorial to Enslaved Laborers"

The degradation, violence, and dehumanization of racialization threads through modernity—its subjectivities, social relations, politics, culture, capitalism, urbanism, architecture, and built environment, especially within institutions like universities that order all of these formations. Mabel O. Wilson will explore how the Memorial for Enslaved Labors at the University of Virginia engages the university’s hidden history of slavery. She shares how the memorial’s complicated design process and public dialogues wrestled with the legacy of anti-black racism in its remembrance of the pain of bondage and the dignity of this enslaved community. Her talk asks, "How can commemoration serve as a means of repair and care for those living in the slavery's wake?"

Mabel O. Wilson is the Nancy and George E Rupp Professor of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and a Professor in African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, where she also serves as the director of the Institute for Research in African American Studies. With her practice Studio, she was a member of the design team that recently completed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia. Wilson has authored Begin with the Past: Building the National Museum of African American History and Culture (2016), Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (2012), and co-edited the volume Race and Modern Architecture: From the Enlightenment to Today (2020). She is a founding member of Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?)—an advocacy project to educate the architectural profession about the problems of globalization and labor. She is the co-host of the podcast Black Lives in the Era of COVID 19, a close look at the impact of the virus on New York City communities. For the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, she was co-curator of the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America (2021).

Devon Mihesuah, an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, is the Cora Lee Beers Price Professor in the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas and is the former editor of the American Indian Quarterly and the University Nebraska Press book series, “Contemporary Indigenous Issues.” A historian by training, she is the author of numerous award-winning books on Indigenous history and current issues, including Recovering Our Ancestors’ Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness, that was recently named the Best Indigenous Book in the World by Gourmand International; American Indigenous Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism; Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero; Choctaw Crime and Punishment: 1884-1907 and American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities, as well as seven novels, most recently Dance of the Returned that was published in September 2022. She oversees the American Indian Health and Diet Project at

Devon Mihesuah, an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, is the Cora Lee Beers Price Professor in the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas and is the former editor of the American Indian Quarterly and the University Nebraska Press book series, “Contemporary Indigenous Issues.” A historian by training, she is the author of numerous award-winning books on Indigenous history and current issues, including Recovering Our Ancestors’ Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness, that was recently named the Best Indigenous Book in the World by Gourmand International; American Indigenous Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism; Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero; Choctaw Crime and Punishment: 1884-1907 and American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities, as well as seven novels, most recently Dance of the Returned that was published in September 2022. She oversees the American Indian Health and Diet Project at